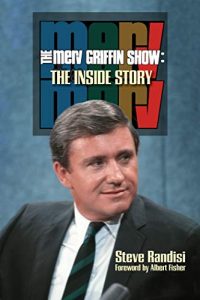

A new book from Steve Randisi, author and lifelong follower of Merv’s shows and work, has recently been released. The Merv Griffin Show: The Inside Story covers the show’s extensive history, features vivid recaps of several “lost” episodes, and shares many fascinating stories from Merv’s life as a singing star and success as a media mogul.

A new book from Steve Randisi, author and lifelong follower of Merv’s shows and work, has recently been released. The Merv Griffin Show: The Inside Story covers the show’s extensive history, features vivid recaps of several “lost” episodes, and shares many fascinating stories from Merv’s life as a singing star and success as a media mogul.

We’re pleased to share this exclusive excerpt from the book. Enjoy!

METROMEDIA MERV

After the demise of his late-night chat fest on CBS (August 1969 to February 1972), Merv was ready to bounce back in prime time.

During the late-afternoon hours of March 9, 1972, nearly a thousand people patiently stood in line outside the Hollywood Palace Theatre to witness the rebirth of The Merv Griffin Show. With only 400 seats available to the public, a multitude of irate fans could be seen scampering in all directions after the pages uttered two dreaded words: “We’re filled!” Located at 1735 Vine Street, the Hollywood Palace was a stone’s throw away from the famed intersection of Hollywood & Vine. “You can’t get more Hollywood than this,” quipped one lucky ticket-holder, taking his seat in the audience.

The old marquee, which had trumpeted some of the greatest names in entertainment, now emblazoned the theatre’s current occupant: The Merv Griffin Show.

Assisted by most of the people who had been with him at CBS, Merv was ready to raise the curtain on his first show for Metromedia Producers Corporation. For Merv, this wasn’t merely a “comeback” after his failed attempt to dislodge Johnny Carson; it was also the dawn of the final chapter in his career as a talk-show host.

The Griffin show had been off the air for nearly a month. During the hiatus, the star and his staff labored mightily to ensure that the Metromedia premiere would be a momentous event. Merv was ready for it. He’d shed nearly 30 pounds, looking nearly as svelte as he did during his best Play Your Hunch days. Without having to deal with the unrelenting stress of network television, Merv was once again at the top of his form.

As the orchestra, still under the baton of Mort Lindsey, struck up the familiar theme music, Merv walked onto the stage wearing the broadest smile possible. To the home viewer, the switch from network to syndication was imperceptible. The only discernible difference was that Merv was now on a different channel.

“This Hollywood Palace lends itself to doing something that dramatic,” said Merv. “But I told my staff: this is a simple talk show. I do not want to do anything spectacular.” As he spoke, the set behind him parted, revealing an elaborate mobile bandstand slowly moving forward.

Earlier in the day at rehearsal, one of its wheels had gone flat. “Did you ever see a band with a flat tire?” Merv laughed. “All my life, I’ve wanted a motorized bandstand.” Now he had one, and he wasn’t going to worry that another flat might mar his opening-night song, “La La La La La La,” a rather unusual choice. Steve Lawrence, the first guest, offered the more conventional “Ain’t No Sunshine, When She’s Gone,” which he had just recorded for the MGM label.

By the time Merv brought out his next guest, Dinah Shore, a slight disturbance could be heard in the balcony. “Move back!” a voice yelled. “Louder!” said another. Merv continued chatting with Shore as though nothing was wrong. As they continued, the grumbling became more vociferous. Obviously annoyed, Shore said, “I keep feeling like somebody’s talking back to me.”

“Just a minute,” snapped Merv. “What’s the matter?” he asked, looking up at the balcony. “You can’t hear a thing I’m saying?” Shore asked incredulously. Soon, the only voices being heard were the ones emanating from the balcony. “Wait a minute,” said Merv in frustration. “One spokesman at a time. You can’t . . . what? You can’t see?”

Apparently, the panel of chairs had been placed too close to the edge of the stage, making it difficult, if not impossible, for balcony patrons to catch any of the action. Equally problematic was the less-than-adequate sound system, which had begun to fail during Shore’s discourse.

Merv asked if any stagehands were in the house. There were. “Let’s push this whole thing back,” he ordered, “then we’ll go on with the show.” The crowd roared its approval. “I knew we were going to have a balcony problem,” Merv sighed. “I just knew it.” Shore looked up at the balcony and said, apologetically, “You’re not missing anything!” To which Merv replied, “Oh, yes, they are!”

The next interruption was a pleasant one. “Telegram for Merv Griffin!” announced a plump visitor to the set. It was Dom DeLuise, bearing a lovely bunch of bananas—instead of cocoanuts! DeLuise had been one of the opening guests on Merv’s Westinghouse series. Merv regarded him as a good-luck charm. This time, though, the evening had brought anything but good luck.

Even Merv’s cuff links were giving him trouble. He fumbled with them nervously as he began to introduce the big draw of the night. His expression turned somber. “What?” he said to his producer off camera. “He’s downstairs?” The groans from the audience resurfaced. “Now they’re going to really come get us!” “Stretching” is a television term for filling in time. That’s exactly what the panel did as everyone awaited the arrival of “Mr. Television”—Milton Berle.

Milton Berle was television’s first superstar. In 1948, when his Texaco Star Theatre aired on Tuesday nights, movie theatres closed early, and folks who didn’t own a TV sets found an excuse to visit their neighbors who did. “Uncle Miltie” had made numerous appearances with Merv through the years, particularly on the CBS entries taped at Television City.

Berle said he’d been watching the show backstage. “I haven’t been so thrilled since I won Totie Fields on The Dating Game.” Some of Berle’s wisecracks fell flat. “Hey, you died,” he barked at his fellow guests, “Now let me die.”

“You were never funnier,” he told Merv, commenting on the opening monologue. “And that’s a shame.”

Berle seemed to be taking over as host, critiquing Merv’s jokes and calling for the commercial breaks. His temerity came to a screeching halt when the next guest, Dionne Warwick, accidentally knocked a table onto his foot. “I’m suing Motown,” barked Berle, as he took Warwick’s coat. “Milton,” said Merv sternly, “can I run my own show?” Berle shot back a look that communicated: “Can you?”

In one of the show’s brightest moments, Warwick, Lawrence, and Griffin did an impromptu rendition of Bachrach’s “What Do You Get When You Fall in Love?” while seated on the panel. After the song, Warwick began speaking softly and the ire of the studio audience resurfaced. “Louder, louder!” they shouted.

The sound in the studio was loud enough for the nation’s critics. “It’s the Same Old Merv Griffin,” observed Rex Polier in his column for the Philadelphia Evening Bulletin (March 14, 1972). Polier noted that Griffin’s new show bore a remarkable resemblance to the old one. Which old Griffin show? “Take your pick of either his earlier syndicated one or the show he just recently bombed out from CBS with,” wrote Polier. Griffin’s guests, in particular, failed to impress the critic. Polier felt that Dom DeLuise came off as simpering, while Milton Berle was too overpowering.

“It is a little puzzling what Griffin thinks he can accomplish with a new talk show that he couldn’t in three years with CBS with a contract that gave him everything but the executive dining room,” Polier concluded. “He doesn’t appear to have any unplumbed depths.”

TV Guide observed that Berle had insulted his host venomously. In reality, it was simply a case of Berle being Berle. Even if Uncle Miltie’s zingers had been delivered maliciously, Merv would have handled the situation with his usual aplomb. Over the years, producer Bob Murphy would frequently attest that Merv wanted all his guests to outshine him. “He loved to listen and he didn’t try to top you,” said Murphy. One can view thousands of Merv’s shows and not find him even remotely rattled by a seemingly hostile guest. On the rare occasions when someone may have made a snide remark, the audience almost always sided with the host.

The Metromedia opener had been an unrestrained show. Even with all its near calamities, Merv would liken the experience to a vacation in Hawaii compared to his last days at CBS. The new show embodied an energy that was lacking during those awful last episodes on the network.

What the critics didn’t mention was that in several major markets (including New York and Los Angeles), the newly syndicated Griffin show had performed remarkably well against its network competition.

The Merv Griffin Show had cautiously embarked on a new and arousing chapter, one that would prosper for the next 14 years.

Excerpt from The Merv Griffin Show: The Inside Story by Steve Randisi