Steve Randisi, author of The Merv Griffin Show: The Inside Story interviews Ray Sneath

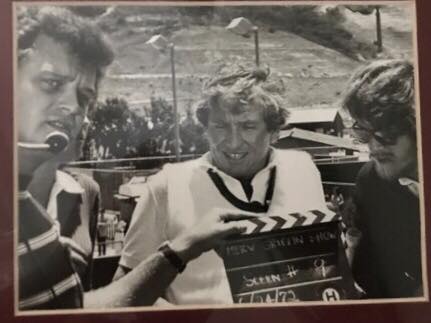

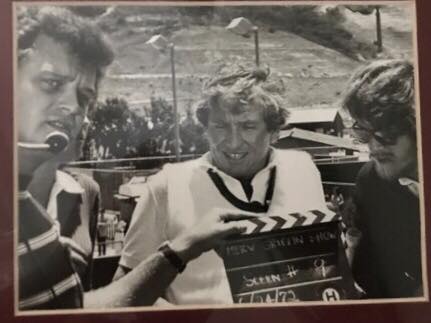

Stage Manager Ray Sneath holding the slate for The Merv Griffin Show episode with special guest Princess Grace of Monaco in 1976.

Born in Glendale, California in 1945, Ray Sneath has worn many hats behind the scenes of the television industry, beginning as a carpenter, and then working as a grip, property master, electrician, stand-in, stage manger, Director of Creative Development, and Vice President of Game Shows and Variety Shows. He was an integral component to many acclaimed series, including The Smothers Brothers Comedy Hour, The Carol Burnett Show, and, ultimately, The Merv Griffin Show.

In this rare interview, Ray recalls his association with the inimitable Merv Griffin, with whom he worked closely on a daily basis for more than two decades.

SR: When and how did you first meet Merv Griffin?

RS: It happened while I was working at Television City in Hollywood in late 1969 when Merv brought the show out there for a week’s worth of shows, to be followed by a week of shows in Las Vegas. I was assigned to him as his stage manager. I must say that I’d never met Merv and did not know who he was. I arrived for work early, at Stage 43, the old Judy Garland stage and also the one where I’d worked with the Smothers Brothers. I went in early to make sure that the set was getting together, lighting was doing their job, and so on.

SR: It’s been said that the stage manager position is a very substantial one in television.

RS: Yes, the stage manager is the person who’s going to be responsible if certain things are not done. This was a talk show, and I’d never worked on one, but it was pretty simple. The set wasn’t very big, and things were going well. Then Merv arrived on stage. I went over and introduced myself, and it seemed as though I instantly had his attention—because that’s the type of person he was. I said to him, “How about a tour of your new place here?” And he said, “I’d love it!” I took him around, introduced him to the crew, and he seemed very interested in everything. We were both working for CBS. I showed him the dressing room I’d gotten for him, and it turned out to be a very easy first meeting. The rest of the afternoon was taken up by rehearsal, and around 3:00 p.m. I went over to ask him what song he wanted to do. This is important because there are a lot of things involved, like cue cards. I brought him down to rehearse the song with Mort Lindsey, and that also went well. Then came makeup and wardrobe. When you’re working with someone who is well known, they can either be nervous or busy in their thoughts. But with Merv, you had his attention, so it was easy for me. I also met [announcer-sidekick] Arthur Treacher. We put a little twin bed in his dressing room in case he needed to relax if he got there early. Arthur and I hit it off immediately; he was like the grandfather I never had. He always addressed me as “Young man!” He was so theatre-disciplined and a joy to work with. He liked to be on time. My mental picture of Arthur is of him looking at me with a smile and pointing to his watch with his right index finger, meaning are we going to go on time? He was very disciplined.

SR: What are your recollections of that first taping with Merv?

RS: At the start of the show, I slated it, as we always do. And with the band playing, and Arthur’s announcement, Merv came out to applause. He did the monologue, which was fine, and everything was going well. After the commercial, I walked him over to the panel, so he could get the feel of it, at stage right, which was the normal way of talk shows back then. After the commercial, it was time for the first guest, and I timed him down. Merv liked a three-minute count down. I had little cards that I used, marked three, two, one. Sometimes he would forget to button his jacket, and his tie would be falling out. So I had a little sign that said “coat” in order to signal him. We used these little codes, and developed a way of working on the job that first day. With a variety show, there’s a script and they stick to it. A talk show is not a scripted show. It has a run-down, and that’s it. People come out and do their segment, and of course we’d juggle segments. I found this format invigorating. It was done live, in the studio, and I loved it. We finished the show and everything just went really well. At the end, after the credits rolled, I walked him across the stage where he said good-bye to a few people. He didn’t say too much. But when we got up to his room, I said to him, “Well, this was really cool! We’ve got more shows to do. I’ll see you tomorrow.” And with that, Merv said, “Get in here!” And I thought, uh-oh, what have I done? He looked at me right in the eyes and said, “What did you just do?” And I couldn’t think of an answer. Merv said, “Ray, I have never done this show to time. It sometimes takes us two or three hours. You don’t know how hard it is to sit there, waiting for the cameras and set changes, while I’m there with the guests. I’m getting my notes, but at the same time, it just falls down. We lose all the momentum. But that didn’t happen tonight! Did we just do a ninety-minute show?” And I said, “Oh, yes!” I explained that this was my first talk-show experience and how much I enjoyed it. And Merv said, “We’ll talk tomorrow.” And that was my first day with Merv.

SR: What were your thoughts at this point?

RS: I must admit that on the way home, I had a chill. I thought this man is out of New York, and I’ll probably never get to work with him again unless he comes out here. But I am so looking forward to working with him for the next two weeks. He’s just so talented and so together. The next day I came in and found that Merv had arrived early. He said he really wanted to work with me, explaining that his show was based in New York, and that I should think about it. The rest of the week we were busy doing the show and didn’t get to talk too much. But by the end of the week, everybody on his team—the writers, producers, and staff—that had come out to Hollywood with him, and myself—got very excited about going to Las Vegas and doing the show from there. Merv became like family. You work so closely as you rehearse, do the show every day, and then at nighttime, its out on the town. I was part of his entourage; we’d go out and see the entertainers, then come back and talk. Sometimes we’d talk until midnight. And of course I’d have to get up early for rehearsal. I didn’t bring Merv in until about eleven, so he could get more sleep.

SR: How did the Vegas tapings differ from the Hollywood tapings?

RS: In Vegas, we worked in the main show room, rather than a studio, which we were used to. We weren’t exclusive. The night show, which featured Tom Jones or whoever was playing there, would share the stage and dressing rooms with us. We’d arrive in the morning, and they would start putting the set together. Rehearsals would start with Mort Lindsey and the orchestra, and the people who were going to be on would come in and rehearse.

SR: This was in the fall of 1969? Were you still with The Carol Burnett Show at this time?

RS: I was with CBS as a stage manager, which meant that I was a freelancer at their studio. They had four stages, so if Carol Burnett needed a stage manager because one was sick or something, I would work for her, or Danny Kaye, or Red Skelton, or certain commercials they would bring in to do. I did the Rose Bowl Parade, and many things that CBS was involved in. I worked for CBS, the same as Merv did. There were only three networks in those days, ABC, NBC, and CBS, so everybody worked for a big company. I had a wonderful time with CBS. I also got to witness six months of the space program, with the astronauts going to the moon, and working with Walter Cronkite during the live coverage of the lunar landing. It was an exciting time.

SR: So within a relatively short time, you cultivated a good working relationship with Merv…

RS: During that weekend in the Las Vegas, it became obvious that we worked well together. At the end of the week, Merv said to me that he’d been talking with Bob Shanks, the producer, about me. During every commercial, I’d go over to Merv and check if everything was going smoothly. He might say, “I need another guest,” and then I’d let Bob know. We saved a lot of time without Bob having to go up to the desk. And I could let everyone on the show know what was going on. We could make it up as we went along. I had a radio transmitter, rather than a wire, so I could tell everybody as to who would be coming out next—and whether it was going to be a normal entrance, a cross to the desk, so lighting would know, the director would know, and Mort would know. Or I could indicate that there’d be a change, whatever. And that’s how it was done. Everything was originated from the stage. Our run-down was strictly that, a run-down that we could use or go off of. And it gave Merv the freedom to pace that show. Because, make no mistakes, he was the man who paced the show when he was on that stage. He was a total showman! So, by the end of the week, he really wanted me to be a part of his organization. He said he would check back with me on the telephone.

SR: When did you next hear from Merv?

RS: One day, at home, I got a phone call. It was Merv, from New York, and he said, “I’ve got Bob here on the other line.” And this kind of surprised me, because in show business a lot of things are said, but they never happen. He said, “Ray, I really want you to work with my company,” and that’s when he kind of opened up and told me his dream. He said, “I really want to get away from the network someday. I don’t want to work for a network anymore. It’s too restrictive in creativity. And I also want to own my own production company, which I do now, with my producers and writers. But I want to do it all someday, and that’s where I need you because you know that area—the world behind the camera. That’s where I’m heading and I’d like you to be a part of it. But right now, I’d like you to come back to New York and direct my show!” Now, I’m 24 years old at the time. And I said, “Merv, this is such a big thing to offer!” He invited me, for starters, to visit him in New York to see his operation. I had a vacation week coming up, and I told him I’d never been to New York and would need a place to stay. He said, “No problem. It’s taken care of.” I sat down with him went I went back there. I watched the show everyday and saw the inner workings of it. At the end of the week, Merv, Julann, Tony, the Treachers and myself all went out to the Griffin farm in Califon [New Jersey]. Although Tony must have been around ten at the time, he impressed me with his manners and the way he handled himself. I got to know Tony that weekend and really liked the family experience. On Sunday evening, after this great dinner Julann had made, Merv took me into this gorgeous little den; it was time to talk! “Well, you’ve had a week to look around and see my operation. What’s your answer?” And I said, “Merv, there isn’t anything I see that I don’t like. I like your operation, and I’d love to work for you because I think we work well together. But I have to say no. He looked at me without getting upset and said, “Tell me why.” And so I told him: “In California I have the freedom to drive around in a car, to the mountains, to the beach, and that’s a freedom I’d never had until I was 16 when I first got a car. It would be hard for me to leave that, and also my mom.” I was taking care of her. I said, “But it’s really that I don’t think I could be happy in this kind of environment because I’m really kind of a small-town kid. In New York, I’d have to live in an apartment somewhere, and I’m used to a house. And I love working with people, including you. But as a director on a talk show, I’d be going into a control room, in a dark space to direct the cameras, and I don’t think I’d be happy personally. If this were true, it would affect what I’d be doing for you and your company.”

And I think what impressed Merv, which I didn’t know, was that he realized it was taking so much longer to do the show the old way, with Kirk [Alexander] in the booth as the director. Nothing negative about Kirk, he was a good director and I enjoyed working with him. He was certainly easy to be around. But that’s the way I thought a talk show should be done, when it originates from a stage like that and not out of a script.

SR: And Merv kept you in mind for the stage manager’s position when he moved to L.A. in the fall of 1970?

RS: We kept in touch. Merv would call me about once a month. Sometimes Bob would be on the line and we would talk about the future. We talked about how Hollywood had really become the capital of entertainment by that point. New York had gone kind of sour. Three other talk shows [Carson, Cavett, and Frost] were being produced, and if you had one person on, they were going to turn up on the other three shows. It was crazy. But CBS had spent a lot of money on his control room in the Cort Theatre. So this was going to be a tough one. But if Merv could pull this off, and move to Hollywood, he wanted to know if I would be his stage manager. And, at that point, I said, “Absolutely! I can’t wait.” Finally, one day, he called me and said, “I’ve got good news! They’re going to do it! They’ve spent all this money, but they’re going to do it. I’ll be moving my show to Hollywood.” He told me who he’d be bringing with him. He was excited and so was I. A few days later, CBS called me into the office and informed me that Merv Griffin, who would be moving his show to the west coast, had requested me as his stage manager. And I said, “Wow! I’d love to!” And that’s how we started working together on a regular basis. Of course, by this time, it was a family that I respected. I knew Julann and Tony and helped them with their move to the place they rented in Beverly Hills. They’re incredible people and I was very fortunate to have them in my life. We were now working at CBS Hollywood, and we’d travel the show, back to Vegas. It was extensive on travel at this point. We went through a change of directors. Dan Smith left, and finally, Dick Carson was the director—the best.

SR: In early 1971, Merv abandoned the traditional desk-and-sofa format. Did this present any challenges for you as stage manager?

RS: I was all for it, because, like Merv, I like change as well. This kind of started with a conversation we had in his dressing room between shows. Merv said he felt kind of anchored by the desk. We talked about the blue cards with his notes on them, which he never used. But my first concern was that he wouldn’t have any place for his notes. So we put that little coffee table in front of him. And we talked about the miking, which was not a big thing. But the big thing was that to have two cameras out on the ramp, which was in the center of the theatre, and with Merv in the center, the cameras would be on stage left and stage right, which was good for the audience, because that’s who you’re playing to. We had four cameras; two on the ramp—close-up and long—and then one stage left and one stage right. Later, our art director, Henry Lickel, made that familiar pie-shaped rolling platform about six or eight inches high, which matched the old band platform. A lot of people I knew and had worked with earlier, like Henry, ended up doing things on Merv’s show. Because, later on, when he established TAV, he had to hire a lot of people.

When Merv was doing the show, his camera was camera one, which was stage right and he’s at the desk. And I was always ten feet away, within eye contact. So the change in format really didn’t make it hard for anybody, and it was a great freedom for Merv. The only problem occurred when I was needed to get something to him. He was seated in the middle, with people on his left and right, and everybody was talking. I didn’t have his eye contact.

SR: At CBS, you devised a way of letting Merv’s interviews run longer without breaking for commercial, and then splicing in commercial pick-ups in post-production. How did that practice come about?

RS: There were times when I could see how hard it was for Merv during an interview that would really start to get going. He would peel the onion down to where he was finally getting what he wanted out of a guest. And I’d be throwing commercials at him because that’s what the booth was telling me to do. When the show was down during rehearsals, we would talk about things like this. And I said, “You know, Merv, when you’re really into an interview with a someone who was slow getting warmed up, we can just keep it going. I could give you a sign with my hands. I’ll let the booth know that we’re splitting the commercials, so they can back-time the next segment, and then at the end, we’ll just pick it up. If you’re going to do two segments with a guest anyway, why not keep it going and let them warm up even more?” He just loved this idea because, as an interviewer, it freed him up.

SR: Merv often talked about the lavish courtesy bar he provided for guests at the studio. He once joked that his show was feeding half of Hollywood!

RS: That was at CBS during the first year he was out there. Illson and Chambers were the executive producers at that time, and I think they came up with the idea for the bar. I could be wrong, but I think it was part of the new team’s idea to put in a nice green room, the holding area for guests. And they wanted a very nice one, with a bartender and food catered from Chasen’s. This was on Stage 43, where we had first met, the former Judy Garland stage. There was an area, if you stood center stage, and looked down stage right, there was a whole section curtained off that made a good-sized area for a green room. It was close enough to the stage that if someone was needed, the second stage manager could go fetch them and get them up there. I had always spent my time out in front of the audience with Merv. So I was never really in the green room that much. Of course, I’d go if I had to meet someone, but I didn’t hang out there. I remember things that happened because of that. One thing was that we had a lot of freeloaders. There were even people from other stages that would come over and hit the green room because we had the best food! Another thing I remember about the big buffet was the camaraderie, which was conducive to drinking. I had spies in the green room that would tell the second stage manager, John, that so-and-so has been drinking and she’s kind of tipsy! Then, during the commercial, I could go up to Merv and alert him that so-and-so had been drinking a lot. I would at least let him know, and he’d kind of protect them. He wasn’t about to expose them or make jokes at their expense. But he would also know how to have fun, without making it look like someone was drunk. Do you know what CBS, with those four stages, had for a commissary? A lunch truck! This guy supplied coffee for all the stages. He also had cement pad with an awning where you sat and had your lunch or dinner. It was amazing.

SR: And there was the Farmers Market right next to CBS…

RS: Yes, and you could walk over there and get something to eat—if you had time. But now we had Chasen’s catering the green room at The Merv Griffin Show. When that happened, the word got out, and we had people from Carol Burnett’s show, Red Skelton’s, or whatever show, coming over to our show and they’d be helping themselves. These were writers and directors, not crew people. I am sure the food bill got very high.

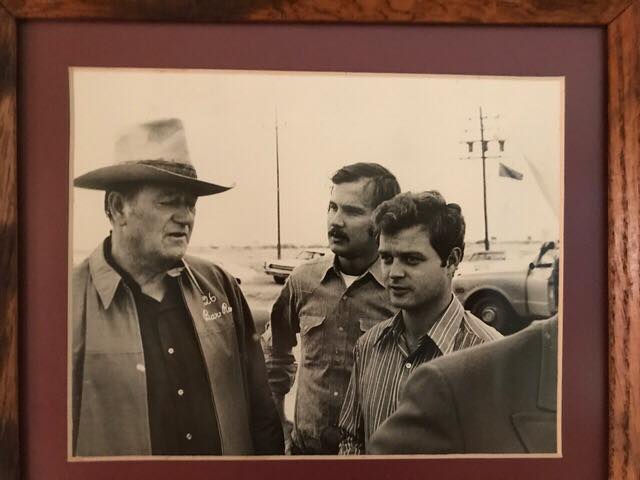

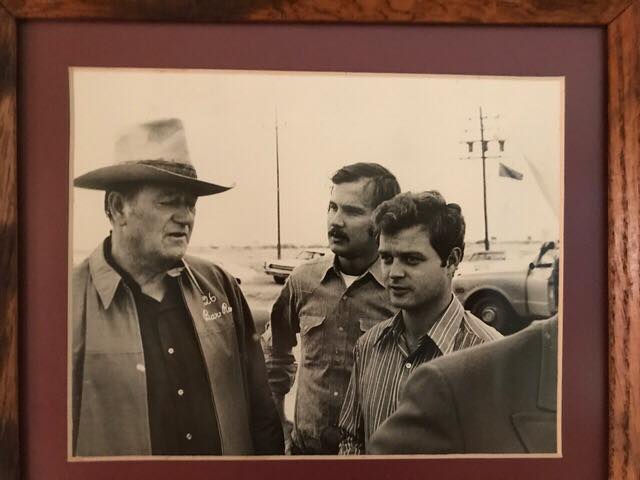

SR: With the advent of theme shows at CBS, such as the “Salute to the Silent Screen,” Merv also did some epic, on-location episodes like “The Duke and I.”

RS: That wasn’t one of the shows that we were going to do the traditional way. We started talking about it in the dressing room, which was actually more like an office or living room. Merv knew that John Wayne was going to do this bull auction in Phoenix, where he owned this huge, huge ranch. Merv said he really wanted to originate a show from there. And as I think back, we didn’t do it on videotape and we didn’t use our crew. It was shot on 16mm film with a dual sound track. In those days, we didn’t have little video cameras, although we would get into that later. So to get the show out of the studio and do something different, we put this together. We ended up taking Rick, the cameraman and his equipment, and Jim, the soundman. We were really on a shoestring. I suggested getting some aerial shots, which were fun. I asked Mr. Wayne if he would give me a tour because I wanted to select some good spots to shoot. And he was really cool about it. We went out to this huge, dugout that was actually the food bin where the food was stored for his animals. He showed me things of interest on the ranch, like where the cattle would eat and sleep. I asked him, “Just how big is this place? I don’t see any fences.” And he pointed and said, “See that mountain back there? I own to the mountain!” I told to Merv and he wound up using it. We didn’t have makeup buses, so we did the show without using any makeup. It turned to be a really fun episode. But when we brought the film back, it had to be edited. This wasn’t something that could just be thrown together, like videotape. It was all done on location. We ended up putting it all together, and I think Jim got credit as director. It aired and turned out to be a pretty good show. This was a good example of let’s get away and try something different. This led into other location shows.

SR: In 1972, Merv moved the show to the Hollywood Palace Theatre on Vine Street in the heart of Hollywood.

RS: The Hollywood Palace had a great history and it was a wonderful place to work. We did a lot of good shows there. Merv was renting it from ABC. We had our crew, which was from ABC; they were network cameramen, audio, booth, and technical directors. And then the stage crew was ordered out of Local 33 IATSE, just as it’s done at the studios. Merv had what’s called “above-the-line,” meaning that his staff, production people, producers, director, writers, myself, were employed by him. But everybody who worked on stage, or in the control room, actually worked for ABC, just like the crew we had at CBS. Merv basically four-walled the theatre. He took the network crews, and paid them accordingly; that was a “below-the-line” arrangement, and they were paid through his production company. That was his deal, because he owned the show.

SR: What do you recall of the move from the Hollywood Palace to TAV, Merv’s new studio, for the 1975-76 season?

RS: That was a big-time move. Now we had to put together a new crew. This was a whole different contract. A lot of these people worked in film, and that involved Local 44, 728 – the Electricians Union, and so on. It was fun because we had to fill a lot of different categories. Merv would now control, and own, above-the-line, below-the-line, the theater, and the post-production center, which meant a huge difference. It represented a major leap in Merv’s growth. He even owned the cameras. In my time, I knew a lot of cameramen, and I recommended a lot of people, audio people. And when people worked for Merv, they generally stayed for their career. If you’ve ever looked at the names on Jeopardy! or Wheel of Fortune, you’ll see that lot of those people started with Merv years earlier. One of the best things about not being with a network is that you can correct things that went wrong. And if you have a crew that you don’t like, you can move them out and bring new people in. The name of the company, TAV, was Trans American Video.

SR: And there was a whole new look to the show…

RS: Henry [Lickel] built the new set. I had worked with him on All in the Family at CBS. He became our art director. Because Merv owned the building, Henry was able to build an upstairs dressing room in an attic that was really cool. A big front room with a sectional couch where Merv could have all the interviewers come up and be comfortable to discuss the notes before the show. There was also a separate makeup room. There was also a door that you could push in the wall; it opened, and there was a window where you could look down on the stage. We had a green room down the hall that I helped Henry design. The new green room was much more sensible, about 20 by 30, with a Paige who would make a cocktail for you. But there were no hor d’oeuvres or big buffet meals. And that was good because people were now quieter and they’d be paying more attention to the show on the TV monitor.

SR: The TAV years were a time of great financial growth for Merv’s various enterprises…

RS: Yes, but with Merv it wasn’t just about money. He liked to see other people better themselves. When we got to TAV, he sat me down and said, “Ray, you realize I own it all. All of this stuff I’ll be paying for, but it’ll also save me money. Why don’t you buy all the lights and rent them to me?” I thought about it because I’d been a stagehand and understood the electrical aspect, the work and maintenance involved. But a few days later, I said, “You know, Merv, that’s really cool. But if I owned the lights, and there were a lot of problems with cables and lights popping out in the middle of an interview, these are things that people can handle for me. But I’d rather just handle what I handle now—the show, and keep it running the way I do.” And he understood that. He said, “I just wanted you to know that I think we’re going to have a long run, and you could make some extra money.” The bill for lighting was over $100,000 a month, I think.

SR: In the late 1970s, Merv would bring his show back to New York for periodic visits. He initially taped at the Ed Sullivan Theatre, and then the Vivian Beaumont Theatre at Lincoln Center. Any recollections?

RS: Reeves Teletape Studios, I believe, owned the Sullivan Theatre. They had the facility, which was already rigged for television. They had a crew, and Merv paid above and below the line. It was nice because everything we needed was right there, and Dick and everybody could just walk into the control room and do their jobs. And the Sullivan Theatre, with all its history, was a wonderful place to work. It was successful for ratings because audiences felt the excitement of New York. We could do additional things outdoors. We checked the stock market, did man-on-the-street kind of stuff, and various interviews outside the theatre. You could stand outside the exit door of the Sullivan Theatre, look down Broadway, and see people like Andrew Lloyd Webber, who could be a guest. And we were right next to Studio 54! So the excitement of going to New York was fantastic. We could bring on big casts from Broadway shows. Merv loved that because he was a variety person. And to have a host who could sing was the greatest. We could do a lot of music-oriented shows, which I loved because I liked Merv as a singer. In fact, I got to pick a lot of his songs! It was almost like give us a front porch, put up a curtain, and we’ll do a show. It didn’t matter where we were.

Now to go from Sullivan to the Vivian Beaumont was interesting because we had the logistics problem of the theatre being so big. It’s a huge place. There, you had to bring in and string all your cameras, your audio and mics, and a lot of other things needed for a TV production. Your booth/control room could be outside, which I think it was. It’s a little harder when you a show to do with that kind of size. I particularly remember a show with all the big band conductors, where we had augmented our orchestra with strings. I was in the middle of rehearsal, and I couldn’t get through to Merv because he wasn’t close by. I had about 45 minutes left of rehearsal before the show, and my last person to work with was Benny Goodman. He’s out there rehearsing and doing it over again and again. And there was Dick, our director, on camera, saying, “Ray, can you get Benny out here. We’ve got to do it!” But Benny kept standing there with the piano player, because he wasn’t happy with the way it sounded. Now I always liked to start the show on time. You’ve got huge audiences that are waiting outside, in the cold or heat, and I’ve always been conscious of that. I had to run a long way to Merv’s dressing room. I said, “I need your help!” I’d never had to do that in my whole career with him. All I said was, Benny Goodman!” And Merv looked at me and laughed because he knew! We went back to the stage together, and Merv greeted Benny warmly and welcomed him back. Then he said, “Listen, you old coot, let’s get this rehearsal going! We’ve got cameras waiting here and they’re getting cold!” He was able to get through to Benny with a sense of humor. Merv could talk to anybody using humor, and get them to move. We got Benny to go out there, and we got a good balance. We got everybody ready, including Merv, and we even started on time! Merv really helped me that day.

SR: You witnessed some iconic performers making their national debuts on Merv’s show. Two that come to mind are Jerry Seinfeld and Whitney Houston.

RS: They were both showstoppers, and they even stopped at rehearsal! With singers, you get to see them before the show actually starts, when you rehearse them. With Seinfeld it was different; he was introduced, and he just went in and did his stand-up. I had his out-cue, Mort had his out-cue and so did Dick in the booth, this way they know when to cue music and start applause. With comedians, you meet them at rehearsal, and you talk to them. You get their cues, or the production assistant gets them for you, and that’s about all you know about the person. You don’t have to rehearse them. During Seinfeld’s stand-up, I was standing next to the camera that covered Merv. And Merv is sitting at the panel with the lights out. He’s watching and listening to this stand-up about 25 feet away. And we were just looking at each other, like wow! We knew immediately that this guy was going to be a star. The way he carried himself, the way he handled people, his look—everything about him. Those were the kind of times where you just knew this person was going to be spectacular. It was Don Kane [Merv’s talent coordinator] who saw Jerry’s stand-up act, and he’s the one who sold him to Merv and at a production meeting. That’s about all I knew. Now with Merv, unless he saw the performer himself—which I don’t think he did—it was all-fresh for him as well. He signaled me that he was going to walk over to Seinfeld, center stage, when the act was over, and talk to him. Or call him over to the panel, because this is a person worth getting to know. Now for a new comedian to come on a talk show, and get that, that’s huge.

SR: You mentioned that you occasionally used small video cameras to record scenes from locales to be rolled into the show…

RS: Those little cameras were fun. We did a lot of stuff with that. I had a little videotape camera that someone had given Merv. It was from some company, Akai or something. He gave it to me, and said, “Here, Ray, I don’t know how to use this. You play around with it and see what you think.” On the next fishing trip with Tony Griffin and some other people, we went to Mexico. And I just started taking pictures. I had fun doing it, and it was initially something just for Merv and Tony. But when we looked back at it, Merv said: “Wait a minute. How will people know what camera we’re using? This quality looks pretty good to me.” Well, it wasn’t quite that good, but it was okay. We then thought, why not bring a cameraman and a soundman with us, and then do these little tapings. And that’s what we did.

SR: Can you imagine Carson doing that?

RS: Johnny was a terrific guy, a fun person on camera. I met him a few times. Of course I knew his brother Dick very well because he directed our show for many years. I had a high respect for Dick. I really liked him. Johnny, I don’t think, was the type of person for flexibility, running around jungles, making it up as you go along. So it was fun doing things like that, which you could never do on a network. They’d have to have a crew of about 20 people out there, with 15 trucks.

SR: There came a time when Merv would tape more than one show per day. How did that development occur?

RS: Merv and I together were the ones who came up with that idea during those dinners we had between shows. I told him, “You could really save a hell of a lot of money. We can do a week of shows in three days.” And he looked at me like I was crazy. “There’s no way you can do a five-day talk show in three days, he said.” I said, “It would be hard for the producers, but they can produce. And it’ll be hard to book, granted. But you’re the one who’s going to be out there for two shows. You’d have to do one show in the morning, and somehow break, have dinner, and then do another show. You can get two shows in one day, and then do only one the next day, which would be a breeze. And then do another two shows, and in three days you’d have your five shows in the can!” He was paying for the stage. He looked at me and said, “Wow! That’s interesting.” Later, we ended up doing it. He didn’t know how long the show was going to be on the air, but over the years, that starting saving millions of dollars. I don’t know if other talk shows ever used that format. That format was also applied to Wheel; that’s why Wheel made so much money. With Jeopardy!, in one day they do five shows! Those are the kinds of schedules that were created.

SR: What do you remember of the time when Merv decided to discontinue the show, which left the airwaves in 1986?

RS: That kind of goes back to when his company was going to be sold. At the time, Coca-Cola wanted to get involved in show business. After they bought Columbia Pictures, Tri-Star, Merv, and another company, I had nothing but game development lawyers in my office and they wanted to learn the business. It was crazy. But at any rate, before all this happened, Merv was saying, “You know, I’m interviewing kids of kids now, and I don’t know if we’re fresh.” The sale came up, which took months, and we would talk about it over dinner. We’d have dinner in the dressing room between shows. His secretary, Madelyn, would order from Musso & Frank, right there in the thick of Hollywood. She would get the dinner after we had done the first show, and it would be in the dressing room all nice and warm. And then the door would be closed. Nobody could ring the bell because he needed that time between shows. During that time, we could talk about the company, fishing trips, or whatever. He had talked a long time about having the place sell. And he’d say, “I’m really getting kind of tired of doing the show…” We had already developed Wheel, and had company people running it. It was pretty much standing on its own, although Merv wrote all the puzzles. After an hour, I would open the door and that would be the time for all the interviewers to come up and prep him for the next show.

SR: How did Merv handle the prospect of leaving his show after doing it so many years?

RS: He transitioned. We knew the show would be closing down. And for the last six months we were on, I watched his transition. We started changing the subject from the show, the company, the production, to more about casinos, gambling, hotels, and putting game shows in casinos. That’s what Merv wanted me to do with him when he sold the company. He wanted to keep getting me into more of a formality with the company. So when Merv made that transition, he wasn’t getting sad; he was getting excited about a new project. It wasn’t an end; it was a beginning.

SR: Did you plan to continue your career with the Griffin Company?

RS: We talked about it. He said, “If I sell this company, Ray, I want you to have a title.” Every time he would move to a new place, the Hollywood Palace, or to TAV, he then wanted to give me a new job—production manager, vice president. And I’d said no. “I’m spoiled now,” I told him. “I like being on the stage with you, doing the show, directing people, and helping steer the company behind the scenes.” And he understood that. Finally, before the place went up for sale, he said, “Ray, you really need a title. And I’ll tell you why. “If I sell this place, it will make a big-deal difference in what you will get. You’ve helped me build the company; you’ve done everything and have had a free hand, but you have to have a title.” Finally, he came up with a title. I was the Director of Creative Development—games and variety—which is what I did anyway. So Merv promoted [producer] Peter Barsocchini and myself to VP positions. Peter became Vice President of movies and I was Vice President of development of creative games and variety. That was the idea when he sold the company. I was going to go with him and create game shows for the casinos.

SR: Speaking of games, did you have any direct involvement in Merv’s game show productions?

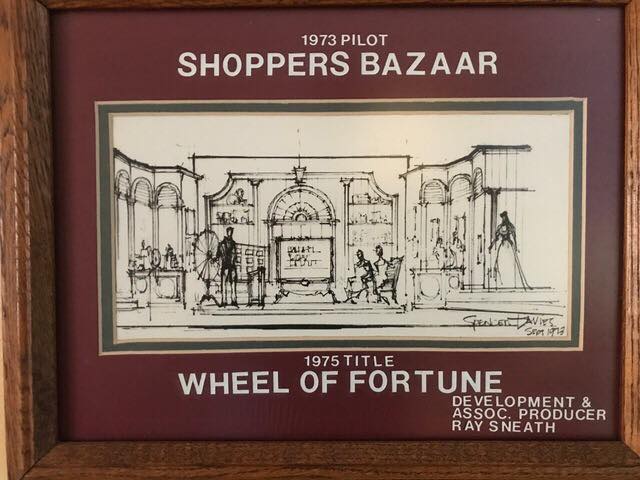

RS: I didn’t come up with anything for Jeopardy! That was all Julann [Griffin], back in New York, before I had ever worked with Merv. I did help bring it back years later. With regard to Wheel, I was down on stage at the TAV Celebrity Theatre, rehearsing with Rosemary Clooney. Merv came down to the set and we sat at the panel. He said, “Have you ever played Hangman?” And I said, “Yes, when I was a kid, I did.” Then he asked, “Do you think you could do anything with that—as a show?” I thought it sounded interesting, and a great idea because you’d certainly learn how to spell. We used the show’s star dressing room as a development room. Merv said we’d need people, and I suggested using the pages working in the audience. So I put together a little group that he and I approved together. Then I got Henry Lickel to build a rolling board to be used for the puzzle. You know what a big, flat TV screen looks like. Well, this was a big black board on wheels. But it wasn’t a blackboard. It was a piece of wood with little cut square holes, the size of an iphone; and there were a bunch of them so you could put cards inside with letters, then cover them up. I had to have some way of doing this to make the concept work. Henry Lickel had it built in the shop; he brought it in to us, and we started working on Wheel. Merv and myself came up with the name Shoppers Bazaar. That was the working title, and I’ll tell you why. Lin Bolen was the head of daytime at NBC, and she wanted a show that could be played in a women’s boutique, a place where women could shop. And in the meantime, we’re working on this show. We don’t have a name for it, but it’s the kind of show where you could plug merchandise. If you remember the original Wheel, it was all plugging merchandise. You went shopping right after you won the round. And to the women at home, this was a fantasy. Now we didn’t develop the show for that. It had already been developed as a game. The original wheel we used was a carnival wheel. We had Henry rent it from House of Props. It was a standup wheel; we didn’t have a wheel on the ground. Marty Pasetta, who directed the pilot, came up with that later. And that’s how we developed Wheel of Fortune. Merv hosted, and we all hosted it in rehearsal. We brought in people off the street. We gave them five bucks, and they got to be in show business. Originally, the game was very bland and it was not working because there were no bad jeopardys. Merv taught me over the years that when you do a game show, you want jeopardys, but you don’t want the audience to blame the show. Blame the people who had the chance. In other words, don’t make the show be mean. It was Merv, who, one day after rehearsal, he said, “You know…what would happen if we put a Bankrupt on the wheel?” And that made the whole game! We put that in, and started doing a lot of run-throughs in the daytime, before work, and that’s how my Director of Creative Development title came about. I also did a variety show for him, a Hellzapoppin’ kind of thing called The Cocoanut Ballroom. It was fun show.

SR: After the original host, Chuck Woolery, left the show, Pat Sajak replaced him. How did Sajak and Vanna White get selected?

RS: Merv used to see people on other shows, and he’d tell me to go home, get a tape and watch them. And I’d see a weatherman or a newscaster, and I’d say to him, “What do you think of this guy?” Then Merv would take the tape home at night and critique it. He did that with Pat. One day he came in my office and said, “Ray, I think I’ve found a host. You know that weatherman who’s on NBC, his name is Pat something?” I went home that night, set my tape machine for the next day, and a couple of days later, sat down with Merv and we started talking. I said, “You know something, I think you’re right. I think this guy is very good!” I would get eight-by-ten glossies of models that wanted to be on a game show sent to my office or Merv’s office. I’d put the photos in pile and keep them in a folder. When it got closer to the time when we realized that we were going to need two new people to replace Chuck Woolery and Susan Stafford, Merv called me and said, “Bring in that folder. But before you do, pick somebody.” The only one I really liked was Vanna. So I put her photo in the back, upside down. I went to his office, and he said, “Who do you think would be good on the show?” I said, “There’s only one. She’s a print model and she’s in San Diego…” Merv started smiling. Vanna’s agent was also sending photos to Merv. And so he said, “Okay, count to three, and we’ll see who we both pick.” He turned over Vanna’s photo—and so did I. Vanna is an incredible person. She’s always on time and cares about people. And Pat is an easy guy to be around, and that comes across on camera. But Merv gets the credit for Pat, because we had auditioned a lot of people. There are a lot of people you try to teach to be a game show host, and it’ll never happen. They just can’t make it. But the games were a lot of fun, and, of course they were the moneymakers.

SR: So you’ve really had a long and prosperous journey with Merv…

RS: I surely had no idea that day when I first met him, and walked him back to the dressing room after that first show, that I would be lucky enough that he’d move the show out here, and we’d have a career together. Working together, in his shadow. It was fabulous. He was a genius. That’s all there was to it.

SR: We’ve heard that as an employer, Merv treated his people well. How would you sum him up as a boss?

RS: All I can say is, I caught the brass ring! The golden ring! You never felt like you were working for him, you were working with him. He never treated you like you were an employee. At least for me, from the get-go, he respected me and listened. I worked with so many people. When you’re stage manager, you work on all kinds of shows. A lot of times, you can be working with somebody and they’re pretty cold. You’re both there for the same reason, you want to do the best you can and get it done, and make it as easy for [the star] as you can. But a lot of times, they’ll treat you like you’re down here and they’re up there! I didn’t have many of those, but there were a few. Merv sticks out above the rest of them because he was just like what you see on the show. He listened to you and was interested in what you had to say.

SR: I understand Merv helped people obtain employment after he sold his company.

RS: That crew was his family; that show was his family. He cared about the people who worked for him. He made sure that a lot of the people, employed on cameras and audio, went with Wheel. He made sure they had careers. A lot of them are still with Sony. When he made the deal for $250M with Coke, he had to stay for two years and so did I. He was into flying by then, and I think part of his deal was that they [Coke] paid for his fuel bill! He was so smart. Merv was a genius, all of his accomplishments attest to that. He was a man you could have a good time working with and he wasn’t intimidating. He didn’t want to be intimidating. So to sum him up as an employer, I could not have had it any better. Merv would be at the top of my list. And I don’t mean in terms of fame or money, but as an incredible human being. He was the Cecil B. DeMille of television. I was fortunate to work in his shadow.

* Photos courtesy of Ray Sneath.

John Wayne on location for taping of “The Duke and I” episode of The Merv Griffin Show, 1971. Pictured L to R: John Wayne, staffer Jim Bradley, and stage manager Ray Sneath.

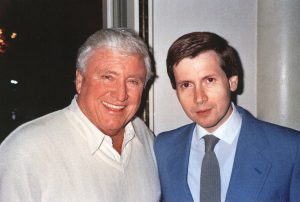

Ray Sneath with Merv and Dino Martin at a tennis tournament in Carmel, CA.

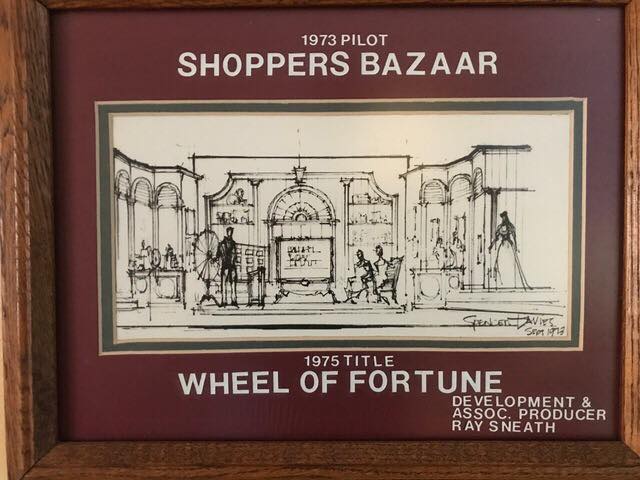

Layout for Merv’s game show “Shoppers Bazaar,” which ultimately emerged as “Wheel of Fortune” in 1975, developed by Associate Producer Ray Sneath.